I’ve been listening to Canadaland‘s isolation interviews. When The Globe and Mail‘s Robyn Doolittle was asked about the strangest thing that she had done that day, she replied that it was doing her normal job as an investigative journalist, working from home (where her partner and young children also are) on stories that have nothing to do with COVID-19.

Like many, I feel constantly distracted by COVID-19

Dolittle’s comment resonates with me. I feel odd working on a series entitled “At Home with Arendt” when I am under a work-from-home directive. Home is a place that I cannot escape right now. Would it be weird to publish a post without acknowledging how weird the world now feels to me?

In the previous post in this series, reflecting on our experience at a conference in early March, Rita makes this comment:

Crisis was a theme in the conference, and I found it hard not to reflect upon the coronavirus crisis currently affecting so many countries. After listening to a radio announcement that many Italians were being quarantined, and being told not to hug or kiss one another, my thoughts went to the effects this lack of connection might have both on the public and private realms.

I had a nightmare that an acquaintance hugged me. In the New Yorker, I read that divorce rates in Xi’an, which is the capital of Shaanxi Province in China, increased drastically when lockdown restrictions were eased. Quarantines can reveal tensions that have been implicitly brewing.

Rita ends her post with this thought: “I do know we need to think carefully about how such crises radically change our connection with the public space, as well as our connections with one another, whenever governments start to decree who can go where.”

Friendship reconnects us with the world

In Arendt’s acceptance speech for the Lessing Prize, which is published as the first chapter of Men in Dark Times, she describes “dark times” as “periods [. . .] in which the public realm has been obscured and the world becomes so dubious that people have ceased to ask any more of politics than that it show due consideration for their vital interests and personal liberty” (12). Arendt argues that friendship has a special role to play in dark times. Friendship, especially speech between friends, re-establishes connections to the world. As Brian Singer emphasizes in “Thinking Friendship With and Against Hannah Arendt,” friendship helps reinforce our humanness in dark times.

The loss of public space makes the world seem more “dubious.” Now the buzz word is “social distancing.” As restaurants and bars, public libraries, board games cafes, and gyms and fitness studios close temporarily, opportunities for social interaction become easier to avoid.

Solitude, isolation, and loneliness

One of my yoga teachers mused that perhaps the slowed down pace afforded by fewer social commitments would have benefits. I, for one, have been sleeping more. Isolation can be an opportunity for solitude, for me to be with myself, to have space and time to think. Although a person need not be isolated to be lonely, with new social distancing protocols in place, isolation can contribute to loneliness.

As Arendt describes in Origins of Totalitarianism, being isolated means we’ve lost the ability to act because we are not with others. Loneliness, however, is “a situation in which I as a person feel myself deserted by all human companionship” (p. 474). Loneliness is another epidemic of our contemporary world, at least in Canada and the United States. Last Thursday I tuned in to the livestream of the Waterloo Centre for German Studies‘ Grimm Lecture. Samantha Rose Hill gave a talk entitled “Thinking Itself is Dangerous: Reading Hannah Arendt Now.” (Watch the recorded lecture here). Hill talked about how Arendt helps us understand how to be alone without being lonely—thinking is a way of telling stories to oneself.

Addressing loneliness

How do we address loneliness amidst social distancing? Maintaining relationships is one way to prevent loneliness. I’ve been calling and texting family and friends more frequently in the past few weeks. I have colleagues reach out just to say hello, or let me know that they are watching Star Trek as a way to destress. (Live longer and prosper!) I find these connections to be truly meaningful amidst the uncertainty over the past week. These interactions, some quite small, help ground me. But, I also wonder about the limits of friendship as a way of preventing loneliness.

Which raises the question: What do I mean by friendship? Arendt bases her ideal of friendship on the Ancient Greek model of political friendship, as exemplified by friendship between citizens. Friendship goes awry, Arendt suggests, or loses its political potential, when we confuse it with intimacy. Arendt’s notion of friendship can seem counter-intuitive because she focuses so much on the Greek model. Intimacy is precisely what many of us think about when we think about who our friends are—at least our good friends, not merely acquaintances or mutual followers on social media.

To return to Singer’s article “Thinking Friendship”: Intimate relationships can provide support and stability for the self, but they may not direct a person to return to the world. This is what separates private or social relationships, for Arendt, from political ones. But, Singer also complicates the sharp distinction between intimacy and political friendship that Arendt suggests in Men in Dark Times. A relationship can be both intimate and oriented toward the world.

New(ish) public spaces

Public space—physical public space—is currently inaccessible for many of us. For now, our public space is almost entirely virtual. Like many others, my daily yoga class has been replaced by a virtual class through Zoom or Instagram Live.

As the world becomes more obscure, friendship can be a source of connection to help re-establish the world’s reality. Care between friends can also help reaffirm the world as something we share in common, apart from our individual private interests. But am I being directed back to the world? Are friendships only a temporary reprieve from loneliness?

Another way to prevent loneliness, research suggests, is through volunteering. Despite the uncertainty and unfamiliarity of the world right now, people are finding new ways to affirm the importance of public space and the world we share in common as new digital volunteer networks emerge to care for neighbors and community members during this pandemic. In an opinion piece on loneliness and quarantine in the Washington Post, Amanda Ripley says that disasters often bring out the worst in humanity. We become afraid, we turn inward. Reflecting on volunteerism, Ripley is optimistic that pandemics need not be characterized by fear.

For me, I am hopeful that we need not forget about the world in or isolation. For Arendt, entering the public realm takes courage. The public realm may be diminished during social distancing, or at least radically altered, but it still requires care. Ripley says, “We have to seize the opportunity, without fear. Viruses may be contagious, but so is courage.”

Feature photo credit

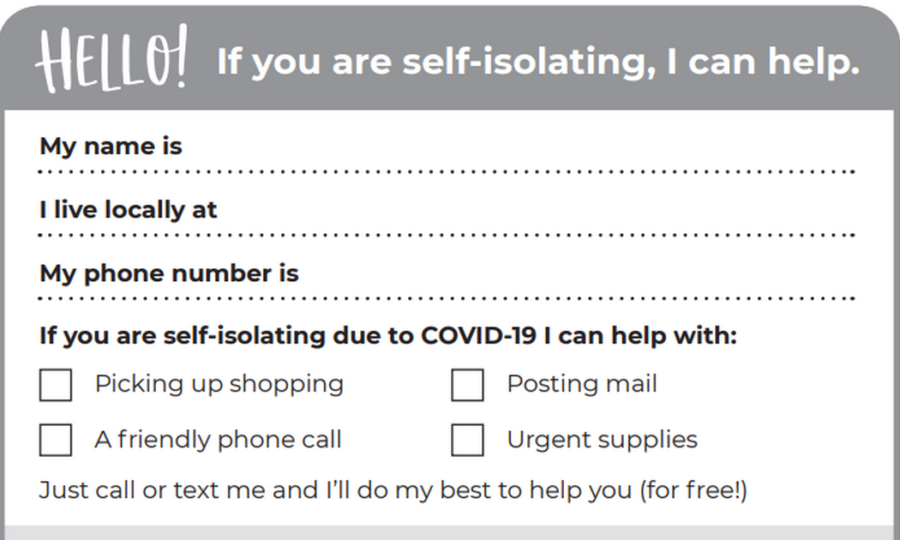

The feature photo is the #ViralKindness postcard.