Humans love to hate on rats. But why? Rats are terrific! Rats, both “wild” and “domestic,” are intelligent (similar to or more than many dog breeds), and “pet” rats are sociable and loving companions. Yet, rats seem more despised than other critters.

One of my parents complains about my companion rats, though they’ve never met. Friends have cringed when I pull out my phone to share pictures. Strangers seem incredulous or annoyed when I encourage them to quit using the term “infestation” because it supports negative representations of rats.

Infestations

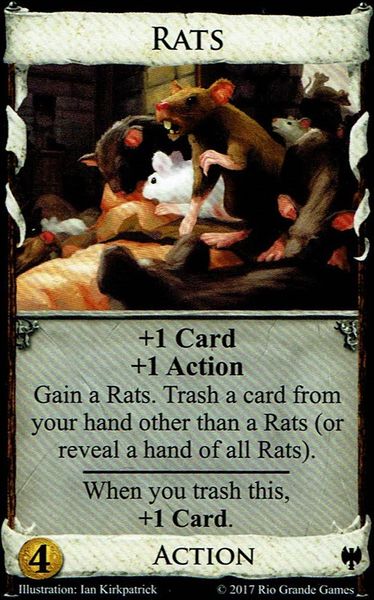

Wikipedia defines an infestation as “the state of being invaded or overrun by pests or parasites.” Rats aren’t parasites, so they must be pests. And they must be invasive. In the deck building game Dominion: Dark Ages, the “Rats” card reproduces itself when played. As you can imagine, this card can quickly “overrun” or “infest” your deck.

Rat reproduction

Yes, rats reproduce quickly and produce many babies, at least compared to human reproduction. Both black rats (climbers, more associated with roofs and walls) and black rats (ground dwellers, more associated with sewers and basements) can breed year-round and have a gestation period of about three-and-a-half weeks (Rat, pp. 30, 32). The quick rate at which rats can reproduce contributes to their attractiveness as a laboratory test subject. They are also favoured for scientific research because they are relatively easy to handle (p. 91). A regime of breeding has produced ever-more laboratory-appropriate animals. But I digress.

Rabbits also reproduce quickly. Rabbits bred to be companion animals or food tend to have a gestation period of around a month. Though I’m drawing on intuition and not a systematic literature review, it seems to me that rabbits don’t face the degree of disgust and dislike that rats do. (Please correct me if I have erred).

Rat sexuality

Excessive

Rat reproduction is not excessive for them, but it seems excessive for us, especially when rats occupy our basements, garages, and transit tunnels. Indeed, rat’s excessive reproduction has been interpreted as an excessive sexuality. In Rat (part of the Reaktion Books Animal Series), Jonathan Burt describes ways in which rat reproduction and sexuality have been described historically as excessive. For example, Roman scientist Pliny suggested that rats bred by licking each other rather than copulation (p. 54). My rats groom each other and me quite frequently, but I am happy to report that thus far, we are pregnancy free!

Abject

According to naturalist Charles Fothergill, the rat “is continually under the furor of love . . . the embraces of the male are admitted immediately after the birth of the vindictive progeny” (quoted in Rat, p. 44). Not only are rats anthropomorphized as sexual beings, but their sexuality is rendered abject, that is, undesirable and threatening.

Rats haven’t been the only creatures whose reproduction and/or sexuality has been thought deviant and threatening. This reminds me of ways in which abject sexuality often indicates social hierarchies. For example, the myth of the black rapist has been used to maintain white supremacy and justify violence against black men by depicting their sexuality as uncontrollable. For another example, the boom of surrogacy in the Global South depends on depicting Global Southern women as having “excess” fertility that is available for use by reproductive travelers. Further, birth control testing in the Global South and policies that use birth control as a government strategy for poverty reduction targeting women of colour and poor women in the US depended on their sexuality and reproduction to be deemed abject.

These examples suggest that depicting a group’s sexuality as excessive and abject serves to reinforce dominance, in these cases, around axes of race, wealth, colonial power, and anthropocentrism.

Why the obsession with rat sexuality?

I’m used to the idea that rats are subject to biopolitical control: their reproduction is annihilated when they are deemed pests, and managed and promoted for their use in scientific research. When and how they are made to live or die serves humans interests. But the obsession with rat sexuality was a new idea for me. Why project sexuality onto rats?

Are rats absent?

As I often do, I turn to Carol J. Adams‘ work to help me think through representations of animals. In The Sexual Politics of Meat, Adams argues that animals serve as an absent referent: We refer to them, but not explicitly.

We render animals the absent referent in three ways: through literal death, through definitions, and through metaphor. Through death, animals are made into food. By definition, animals become meat. Cows become beef; pigs become pork. Through metaphor animals become symbols of human experiences: “He treats me like a piece of meat.” (Adams argues that women and animals are absent referents in contexts of sexual violence).

In Rat, Burt offers a few examples that may fit the absent referent. For instance, rats were associated with witch familiars during the Inquisition (p. 65). Additionally, Victorian representations about rats as lusty and dirty served as a metaphor for the poor masses (p. 75). In this example, it is the poor that are absent in the fascination with rats. I can imagine the conceptual work excess sexuality would be doing in rendering poor people absent in this metaphor.

Rats mirror humanity, darkly

However rat sexuality serves as a metaphor for marginalized groups, it seems that the construction of rat sexuality as abject and excessive indicates a white, colonialist, patriarchal preoccupation with maintaining dominance. One of the main themes in Rat concerns the co-evolution of humans and rats. Rats spread across the globe as humans spread war, trade, and imperial conquest. If rats have a dark connotation, Burt suggests, they mirror humanity’s dark deeds. I’d revise this slightly: If rats have a dark connotation, it suggests something about the harms of oppression and dominance.

Did you know that a group of rats is a mischief?

Rats represent a threat that has the potential to overthrow humans–more specifically, white supremacist, colonialist, patriarchal, industrial, capitalist dominance. If the rat represents evil, perhaps the evils of human domination, colonialism, and imperialism is the absent referent. Perhaps this threat explains why the rat is depicted as surviving humans in the apocalypse, going on to repopulate the earth. Such is the case in Günter Grass’ The Rat.

The biopolitical becomes personal

In late September, Gabrielle went to the vet because I found a lump on her abdomen, near her hind legs. She has a (probably benign) mammary tumor. They are quite common in female rats, especially unspayed female rats. I didn’t think you could spay rats–I thought they were too small!

The cynic in me suspects that rats are not spayed because it doesn’t make “sense” in terms of “cents.” I adopted Gabi from the Humane Society for $15. Who would pay an adoption fee of $75 to cover the costs of spaying?

Not spaying rats may be best for the rats. Anesthesia is dangerous for them. Because they are so small, getting the dosage right can be difficult. Thus, humans control companion rat reproduction by housing rats with members of the same sex. This makes sense. Perhaps it saves cents and lives. But, rats’ reproductive health care also raises questions about the how and why rats are bred to be companion animals.

I am struggling to decide whether to subject Gabi to surgery to remove her tumor. Surgery is stressful for rats, plus the risks of anesthetics. Right now she doesn’t seem to be in pain. She’s playing and eating normally. When I noticed it, the tumor was the size of a grape. The tumor has grown since the initial appointment, and will continue to grow until, eventually, it will cause Gabi’s death.

In the biopolitical organizing logic of fancy rats, a life doesn’t seem to be worth much. Although we’ve only shared our lives for nine months or so, it is difficult to think of a morning without Gabi crawling up my pajamas to give me a nuzzle.

She-Rats

Perhaps I will write fan fiction inspired by Grass’ character, the She-Rat. In the back of my mind, a utopian science fiction story (in the tradition of Woman on the Edge of Time) begins to steep about female rats who take over the world. Well, “take over” wouldn’t be accurate. They survive humanity, and the destruction white supremacist, colonialist patriarchy has brought. They thrive in what we leave behind. Their sexuality is exactly right, for them, on their own terms.

“Rat bodies [. . .] have a dark vitality that, despite all the control and killing, we do not overcome.”

–Jonathan Burt, Rat, p. 149.

Feature photo credit

Rescued rat waiting for adoption at a shelter. Photo credit: Jo-Anne McArthur / NEAVS. Support Jo-Anne’s photography and the We Animals Project.