Teaching with science fiction

I’m a fan of using science fiction in my teaching, probably because I’m a fan of science fiction. After all, Star Trek: The Next Generation was one of my earliest philosophical influences!

Craig B. Jacobsen suggests that science fiction’s “generation of cognitive estrangement makes it perhaps uniquely qualified to provide college students with the critical distance necessary to recognize the complexity of the worlds that they must learn to navigate.” [1] By engaging in discussions that are to some degree distant from our world, students will hopefully be better equipped to think about our world [2]. Similarly, Lisa M. Logan describes science fiction as a safe space for this exploration by providing a metaphor for students to discuss [3].

I find science fiction to be a wonderful way to think about our non-fictional world. Read, for example, some of my previous posts on tribbles, zombies, and space travel. In addition, I’ve discussed vampires and aliens when I taught Queer Theory. Various textbooks I have used for introductory gender studies courses (including my current one) agree, discussing a text I often use: Marge Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time.

Science fiction examples or historical ones?

I had an experience in class that led me to the question: Can science fiction metaphors be counter-productive in the classroom? Consider the following case: A student relates a example we are discussing to a theme in a science fiction film. Another student rebuked them, pointing out that we don’t need to turn to fiction to demonstrate the point being made. Instead, we can look back into Canada’s history to find these examples.

This exchange surprised me, and it has stuck with me. At first, it made me question whether science fiction is as useful a pedagogical tool as I assumed it to be. In thinking about it further, I think the dialogue this exchange could have opened up would be productive. It’s not just a question of identifying oppression or understanding how it operates. Metaphors help us do this work. But, there is a further step: situating oneself in relation to the injustice being described by the metaphor. How are you privileged or disadvantaged in relation to this example of injustice? Especially when we are in privileged positions, without making the connection to “and I benefit from such systems of domination,” the potential of the science fiction metaphor is not fully actualized.

I’m curious about whether other educators have experienced students resisting science fiction metaphors when talking about anti-oppressive work or social justice.

Futurisms

For many science fiction authors, scholars, and fans, it’s the imagination of science fiction that can inspire us to reimagine our world, the ability to imagine other ways of being and doing that can make science fiction an attractive pedagogical tool. This moves us beyond metaphors to resistance [4,5].

Recently, when I consider teaching with science fiction, I’m drawn to Indigenous and Afrofuturisms in science fiction, which I began to read more intentionally last year. According to social theorist and pop culture critic Aph Ko, Afrofuturism provides Black folk a new conceptual architecture for imagining the future [6]. For me, a White settler, Afro- and Indigenous futurisms help me identify when I am epistemically lazy.

According to philosopher José Medina, epistemic laziness is a cognitive vice developed by members of a privileged group by which they lack curiosity about things or issues or contexts that don’t concern them directly [7]. Indigenous and Afrofuturisms launch me into worlds I don’t understand; I become curious about Indigenous and Afro-centric futures.

Maybe I’m sympathetic with my student’s frustration with the way some people engage with science fiction metaphors. Understanding a metaphor isn’t enough; challenging dominance must be part of this work as well. Re-imagining the world, building new conceptual architecture, to use Ko’s phrase, seems more promising.

Sources

[1] Craig B. Jacobsen, “Introduction: Teaching with Science Fiction.” Practicing Science Fiction: Critical Essays in Writing, Reading and Teaching the Genre. Ed. Karen Hellekson, Craig B. Jacobsen, Patrick B. Sharp, and Lisa Yaszek. pp. 7-12. Jefferson, NC & London: McFarland & Co, Inc., 2010. p. 11

[2] Jason W. Ellis, “Revealing Critical Theory’s Potential to Our Students, the Digital Nomads.” Practicing Science Fiction: Critical Essays in Writing, Reading and Teaching the Genre. Ed. Karen Hellekson, Craig B. Jacobsen, Patrick B. Sharp, and Lisa Yaszek. pp. 37-50. Jefferson, NC & London: McFarland & Co, Inc., 2010.

[3] Lisa M. Logan, “Encouraging Feminism: Teaching The Handmaid’s Tale in the Introductory Women’s Studies Classroom.” Teaching Introduction to Women’s Studies: Expectations and Strategies. Ed. Barbara Scott Winkler and Carolyn DiPalma. pp. 191-200. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, 1999.

[4] James H. Thrall, “Learning to Listen, Listening to Learn: The Taoist Way in Ursula K. LeGuin’s The Telling.” Practicing Science Fiction: Critical Essays in Writing, Reading and Teaching the Genre. Ed. Karen Hellekson, Craig B. Jacobsen, Patrick B. Sharp, and Lisa Yaszek. pp. 197-212. Jefferson, NC & London: McFarland & Co, Inc., 2010.

[5] Lisa Yaszek, “Introduction: Women and Writing.” Practicing Science Fiction: Critical Essays in Writing, Reading and Teaching the Genre. Ed. Karen Hellekson, Craig B. Jacobsen, Patrick B. Sharp, and Lisa Yaszek. pp. 149-153. Jefferson, NC & London: McFarland & Co, Inc., 2010.

[6] José Medina. The Epistemology of Resistance. Oxford University Press, 2013.

[7] Aph Ko. “Creating New Conceptual Architecture: On Afrofuturism, Animality, and Unlearning/Rewriting Ourselves.” pp. 127-137. Aphro-Ism: Essays on Pop culture, Feminism, and Black Veganism from Two Sisters. By Aph Ko and Syl Ko. New York: Lantern Books, 2017.

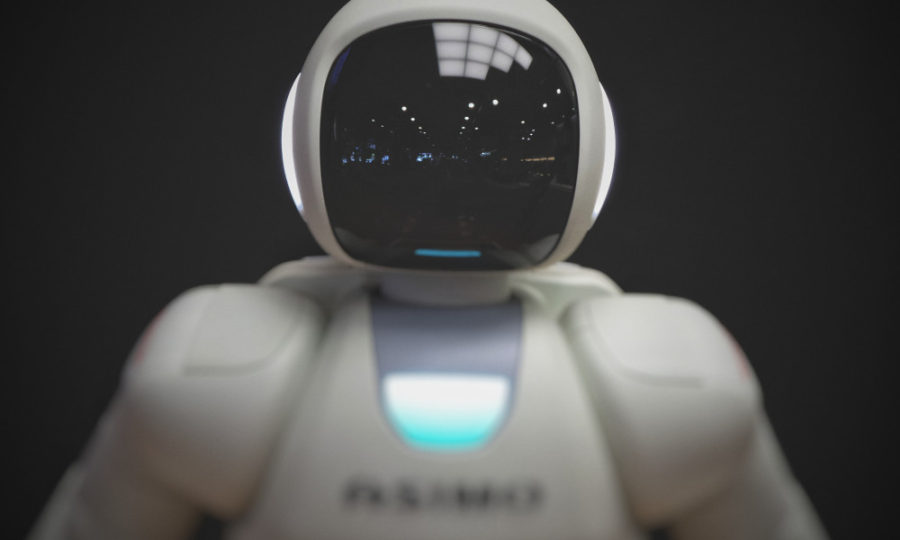

Feature image credit

Photo by Franck V. on Unsplash