In June, Health Canada published the long-awaited regulations on reimbursements in gamete donation and surrogacy. These regulations are important because section 12 of the Assisted Human Reproduction Act (AHR Act) requires that reimbursements must be dispersed “in accordance with the guidelines.” Yes, fifteen years is a long time to wait! The new regulations will take effect June 9, 2020, though contracts entered into between now and then should comply with the regulations.

In addition, Health Canada requests feedback on a draft Guidance Document, which is intended to help people interpret the regulations. Information on how to submit feedback can be found here. The consultation period ends on Friday. Get your comments in!

Positives

Last November, I shared my thoughts on the draft regulations. Some considerations I (and others) raised were adopted. For example, in addition to care for dependents, expenses for pet care can be claimed. Health Canada will also provide sample reimbursement forms. (More on documentation in the next section).

There are two parts of the draft Guidance Document I find particularly helpful. First, Health Canada recognizes that temporally gamete provision and surrogacy extend beyond medical procedures and gestation. Counseling expenses that are incurred in the lead-up to a donation or pregnancy contract can be claimed.

Post-partum care is also included. I advocated for a specified but broad understanding of post-partum to capture varying needs that may arise. The Guidance Document does not specify time frames, but does explicitly emphasize the need for some flexibility to account for context.

This recognition that contexts may vary is the second strength of the draft Guidance Document. What counts as an expense directly related to a surrogacy is partly contextual, which is why some expenses that are not listed in the regulations may be appropriate to reimburse. What counts as a “receipt” may also be interpreted broadly. While a “conventional receipt” is preferred and expected in many cases (e.g., groceries), what is important is that reimbursable expenses are clearly and thoroughly documented.

Concerns

While I applaud the flexibility of the regulations to account for particular circumstances, the language of the regulations and draft Guidance Document give rise to two concerns. First, this process is extremely onerous. Partly it seems onerous because the regulations have to comply with a key value of the AHR Act: the non-commercialization of reproduction.

My second concern is more of a question: what’s the trade-off between ethical protections and effective regulation on one hand, and creating inefficiencies because the of the need to enforce non-commercialization on the other?

According to the draft Guidance Document, “The goal of the AHR Act is to help protect Canadians by setting out prohibited activities related to assisted human reproduction that may pose significant human health and safety risks to Canadians or that were deemed to be ethically unacceptable or incompatible with Canadian values.” Let’s putting aside for the moment disagreements about “incompatible with Canadian values.” Is effective policy achieved when a process is difficult and burdensome for parties to navigate? Could non-commercialization be encouraged without such a burdensome process?

Spoiler alert: I think so!

A burdensome process

A key message of draft Guidance Document is to document expenses. It’s your responsibility! “Your” primarily refers to the intended parents who will do the reimbursing, though much of the labour of documentation falls on the gamete provider and surrogate.

Although the regulations allow for context and individual needs to dictate, to some extent, reimbursable expenses, some categories are off the table entirely. The implication is that these categories might blur the line between reimbursing expenses and payment. And as the draft Guidance Document emphasizes, “Care must be taken by persons making such reimbursements to ensure that they can demonstrate that the reimbursement is not a disguised form of payment that is prohibited by sections 6 or 7 of the AHR Act.”

For example, groceries are a reimbursable expense for surrogacy because pregnancy requires increased and special nutrition, and because intended parents may request certain dietary regimes. But simply submitting grocery receipts is not acceptable. Consider the following statements from the draft Guidance Document:

- “The reimbursement can only be for the cost of the additional groceries required to support a health pregnancy.” (my emphasis)

- “Care should be taken to ensure that such reimbursements are not disguised forms of payment (e.g., paying the grocery bill for a surrogates entire family for the duration of the pregnancy) and thus a possible contravention of the AHR Act.”

Given the emphasis on responsible documentation, what do we imagine surrogates will do? Pay for their “extra” groceries separately from their “normal” and family groceries to help maintain clearly delineated receipts? Highlight costs on a receipt to clearly distinguish them from normal or family groceries? I find this a bit irksome when I submit my travel expenses at work. I often pay for my extravagances (usually decadent desserts!) separately just to make the record-keeping simpler for me. Really my complaint is trivial, because conferences are a few days long, not a year-long, daily affair.

Entrenching anxieties about payment

I think it’s a good idea to be diligent and detailed in documentation. As I tell my teaching assistants: “Track your hours!” It helps to have this documentation when problems arise.

But why is this process so burdensome for reimbursement? It seems like the difficulties exist primarily to enforce the non-commercialization approach Canada has taken toward surrogacy.

The regulations must conform to the AHR Act, so of course they must align with the non-commercialization approach. But it seems to me that the draft Guidance Document goes out of its way to create a labour-intensive process that is intended to squash any hint of commercialization or payment.

Gendered surveillance?

Are we also succumbing to too much gender-based surveillance of providers and surrogates in the name of protecting against commercialization? (Again, let’s set aside the question of whether commercialization is a harm and assume for the sake of argument it is). I keep thinking about “special nutrition,” grocery reimbursement, and ice cream. Say a pregnant person craves ice cream especially during their pregnancy, and not for the pregnancy would never eat it. Seems like a reimbursable expense. Will the intended parents see it as an extravagance? This example is somewhat silly, but I think it gives rise to questions about how surveillance-heavy the reimbursement process can be.

Here’s an example about lost wages. The AHR Act specifies reimbursement for a surrogate’s loss of work-related income requires a written statement from a medical professional “that continuing to work may pose a risk to her health or that of the embryo or foetus.”

Now, the AHR Act is not up for revision. Regulations must comply with it. But I have a question: Shouldn’t a pregnant person be able to take a sick day because they feel too sick to work, even if all things considered the illness doesn’t impact her long-term health or the health of the foetus? If I were a surrogate I could take such sick days and I still get paid because I am salaried, but that’s not the case for everyone.

The examples listed in the draft Guidance Document seem to stress that any reimbursement should really be for serious medical concerns (“e.g., doctor-prescribed bedrest”). Every pregnant person should be entitled to sick days, and some surrogates may be employed in industries where taking a sick day translates into lost wages. My point here is that the strict requirements that require such documentation seem mostly in the service of maintaining the picture that surrogacy is not a commercial endeavor.

Ways to alleviate the anxieties or burdens?

I’m not necessarily convinced that payment is the best way forward. That being said, I worry about how the current regulations seem to focus on sending the message “Hey, we’re not commercial here!” Instead, regulations should focus on helping people navigate assisted reproduction legally.

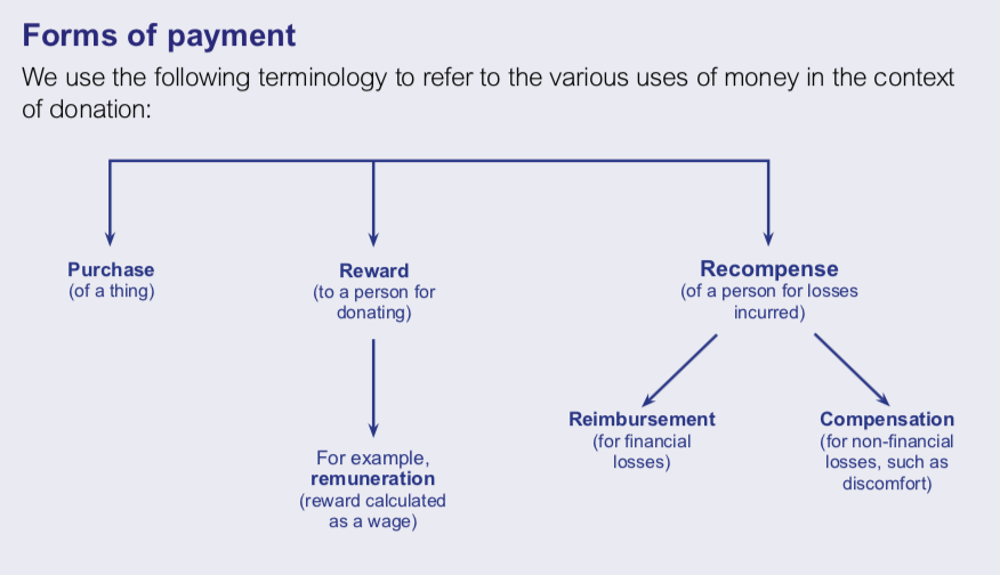

Some distinctions: reimbursement versus compensation versus payment

I find the UK’s Nuffield Council on Bioethics’ distinctions on money comes in medical donations and services to be helpful. Payment is a financial reward. In contrast, recompensation is not about profit. It makes up for losses incurred. This could be through reimbursement, which addresses financial expense, or compensation, which might include remuneration for non-financial losses.

At the moment, I think a regulated compensation model where gamete providers and surrogates are given a lump sum is the best balance between addressing financial vulnerability and complying with non-commercialization. Compensation would be based on reasonable expectations of expenses, and would ameliorate burdens of up-front costs.

Philosophers such as Anne Phillips worry that compensation and payment are only academic distinctions that blur in practice. I worry about this too. Government oversight goes some way, I suspect, in keeping the line between profit and compensation clear. Further, I suspect that a lump sum model would be easier to administer than the current framework.

As a side note, I look forward to seeing the results of Diane Tober’s research comparing regulated compensation in Spain and unregulated payment in the US to see what it tells us about protections for egg donors.

A final quibble about the ambiguity of “altruism”

Some feminist scholars worry that compensation obscures more pressing questions about work and labour. I’d have to say more to address these concerns. One worry is that compensation perpetuates the idea that good donors or surrogates are altruistic. This is a concern I share.

The draft Guidance Document once refers to surrogacy in Canada as “altruistic.” Whatever your view of commercialization, I fervently wish we would stop using “altruistic” as a descriptor. I prefer the more neutral “non-commercial surrogacy.”

Altruism language is confusing because it is ambiguous. It refers to a framework for regulation at times, and at other times it refers to motivations. To alleviate these ambiguities, we should not use “altruism” language, and be cautious when talking about motivations.

To read a longer version of this quibble, see my previous post about empathy and altruism in surrogacy.

Credits

The feature photo is by Fabian Blank on Unsplash.

The graph is taken from the Nuffield Council Report “Human Bodies: Donation for Medicine and Research,” page 5.

As I wrote this blog post, I thought a lot about arguments I read in the anthology Surrogacy in Canada: Critical Perspectives in Law and Policy (Irwin Law, 2018). I especially thought of the following chapters:

- “Should Canada Implement a Flat-Rate Reimbursement Model for Surrogacy Arrangements? Legal and Ethical Recommendations for a Revised Approach to Reimbursement,” by Angel Petropanagos, Vanessa Gruben, and Angela Cameron

- “Surrogacy in Canada: Toward Permissive Regulation,” by Erin Nelson

Order a copy of the book for your library! And give my own chapter a read 😉