Philosophers want their work to matter. At least I do. This hope partially explains my website tagline, “philosophy in the world.” In my first blog post, I wrote, “I seek for my philosophical work to be embedded in the world and in service to maintaining it as a space for speech and action.”

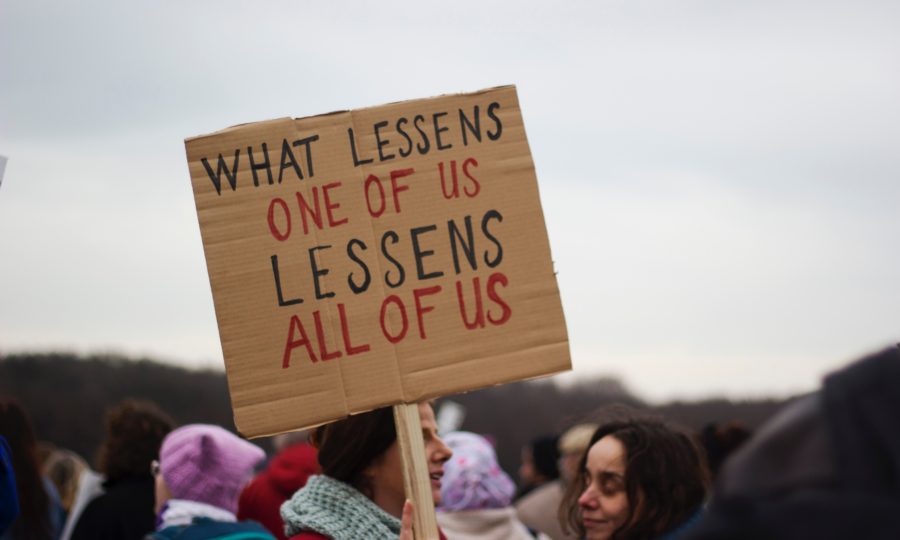

Philosophy can be helpful for public matters. Philosophers often clarify ambiguous or muddled concepts or phenomena. Or, alternatively, philosophers point out that some concepts are treated too simplistically. They help reveal the nuance and complexity behind ideas or phenomena. In either case, thinking philosophically can help generate change.

Recently I have been asking: what kind of change?

Public intellectuals versus public scholarship

In October I heard Dr. Ibram X. Kendi speak about his newest book, How To Be an Antiracist (One World, 2019), at the Racism and Antisemitism Conference hosted by the Hannah Arendt Center for the Politics and Humanities at Bard College. There, Kendi emphasized the importance of public scholarship, not just being a public intellectual: A public scholar writes for public audiences, whereas public scholarship benefits the public.

Social justice work as policy change

The argument that Kendi builds through How To Be an Antiracist focuses on how racism is embedded in and spread through policy. An antiracist is a person “who is supporting antiracist policy through their actions or expressing an antiracist idea” (p. 13). Further, policy change often comes before–and promotes–widespread cultural change (p. 208).

Last month I finished reading How To Be An Antiracist, which provides a more specific definition of public scholarship as aimed at policy change.

I did not need to forsake antiracist research and education. I needed to forsake the suasionist bred into me, of researching and educating for the sake of changing minds. I had to start researching and educating to change policy. The former strategy produces a public scholar. The latter produces public scholarship. (p. 231)

Do I do public scholarship?

I often write about policy, but I am not sure my work quite counts as public scholarship on Kendi’s model. One of my current projects focuses on family metaphors in the discourse around Canada’s Private Sponsorship of Refugees Program. My central claim is that when the public discourse relies on family metaphors to describe political belonging, it makes including refugees more difficult.

When I gave a talk to the Migration Research Cluster on this topic, an audience member asked me what the policy implications of my argument were. “I’m not sure there are any direct ones,” I replied. “I want sponsors to think differently and more intentionally about their relationships, and I want the public to think more carefully about assumptions embedded in family metaphors.”

Philosophy practice as institutional change

I don’t think Kendi meant that every piece of scholarship must directly lead to policy change to be “public scholarship.” The core message, as I understand it, is that educating people about racism is not sufficient for eliminating racism. Education does not necessarily lead to change, or to an antiracist practice.

This sentiment echoes the ways in which Sara Ahmed describes practical phenomenology. Reflecting on a phenomenology conference, Ahmed relates how she noticed that philosophers sometimes seem overly confident about the value of philosophy:

There was a sense that: the moral and political imperative should be for us to become philosophical (as an attitude and not as an institution), and that to “become philosophical” would be a sign of an overcoming of the problems that exist because of our failure to be conscious of them. The becoming philosophical of the world, in other words, becomes a political vision. (emphasis original)

Ahmed does not dispute the importance of philosophical reflection, but she does want to push philosophy towards change. For her, a practical phenomenology is about how practice generates knowledge. She states:

But rather than suggesting knowledge leads (or should lead) to transformation, I offered a reversal that in my view preserves the point or aim of the argument: transformation, as a form of practical labour, leads to knowledge.

In the past decade or so, Ahmed has focused on “diversity work” within universities and addressing institutional racism and sexism. Diversity work, feminist work, makes aspects of an institution visible. Her academic and social justice praxis come together. This seems to me to be implicit in Kendi’s argument about public scholarship. It’s not just that the activity of doing scholarship that helps advance policy reform, but that policy reform and scholarship are mutually supporting and intertwined.

Arendt was a public scholar, but did she do public scholarship?

Like Ahmed, Hannah Arendt finds philosophy and action to be intertwined. Historically, the philosophers’ mistake was to retreat from the world in contemplation and fail to return.

However, I wonder if Arendt is prone to being a public intellectual rather than doing public scholarship. She is one of the most brilliant public intellectuals of the twentieth century (or ever, I might say). What she would make of Kendi’s claim about public scholarship?

Too instrumental? Her emphasis on the need to think and act is part of why I find her work compelling. For Arendt, while action may have a goal, it is not instrumental. It is not a means to an end. Policy change might be seen as an instrumental endeavor. Such an initiative tries to achieve a particular end, whereas action is boundless and open-ended.

Too “social,” in her idiosyncratic meaning of that term? In the Human Condition, Arendt warns us that when policy becomes the focus of action, that individual responsibility is subsumed under institutional rules. A focus on policies can lead to what she calls “rule by nobody” (p. 40).

Teaching practice

Why do Kendi and Ahmed’s claims strike me as so correct, and yet so foreign to how I have done philosophy? These ideas are not at all foreign to how I approach my teaching practice. For the past few years, in both gender studies and in philosophy, I have been crafting learning goals and assessments that think about how the learning we do in class will help students act in the world outside of the classroom.

In the seminar on Arendt that I am teaching, students are facilitating a public conversation about a pressing contemporary political problem for their final assessment. This conversation will be a collective endeavor that is inspired by Arendt’s attempt “to think what we are doing” in the Human Condition (p. 5). And yet the students have also been very explicit that they don’t want to just have a conversation. They want this conversation to support or lead to some kind of action.

Relational knowledge

I’m still thinking through how Kendi’s definition of public scholarship should challenge my philosophical practice. Admittedly, my reading on public philosophy has been relatively minimal. Most of what I have read focuses on how philosophers can engage the public, and also about how public concerns should shape philosophical practice. This doesn’t quite capture Kendi’s challenge, I think, that education for social change cannot simply be about changing minds (or hearts).

A point I find particularly helpful is Jeremy Bendik-Keymer’s argument that public philosophy is relational knowledge, which he contrasts with both theoretical and practical knowledge. It is done in and with a community of non-academics. This too is Sara Ahmed’s beginning point. Everyday feminist work, everyday feminist living (because we cannot forget being at home is part of living, and involves homework) creates knowledge. See Ahmed’s Living a Feminist Life.

I’ve been doing the slow work of building relationships with people and organizations who work with refugees. Most of this work comes from my involvement in an emerging social enterprise, a commercial kitchen co-op. One way I have been challenge to think about doing public scholarship is to integrate more my on-the-ground work with my philosophical work. Perhaps this will be my beginning point.

Credits

Feature photo by Micheile Henderson on Unsplash