The family is at the heart of neoliberalism. Thus argues Melinda Cooper in her 2017 book Family Values. Usually when I hear the term neoliberalism I think about the individual and personal responsibility. Yet, Cooper demonstrates, the family is central to its operations and maintenance. I think Arendt’s critique of the family can be especially helpful in illuminating this claim. But, she also naturalizes the family in a way — similar to neoliberalism.

Personal responsibility equals family responsibility

Neoliberalism is a loaded term, referring to a set of economic policies and a broader ideology that permeates contemporary social and political life in the United States, which is Cooper’s focus. Cooper is especially interested with neoliberalism as a set of policies that emerged from the University of Chicago and some other universities.

Neoliberalism shares with liberalism a focus on the individual as a rational agent, whether it be economically, morally, or politically. But unlike liberalism’s emphasis on the common good, neoliberalism focuses on personal responsibility.

Personal responsibility under neoliberalism has a specific connotation. It is less about integrity and conscience, which I associate with Arendt’s notion of personal responsibility. (For a sense of Arendt’s view, read her essay “Personal Responsibility under Dictatorship” in Responsibility and Judgment). For neoliberals, what used to be the responsibility of the state, such as social assistance, becomes the responsibility of the individual.

The family wage

But this notion of personal responsibility, Cooper argues, is really a matter of family responsibility. Although neoliberalism focuses on the individual, it really refers to a (male) head-of-household earner. The maleness, and whiteness, of the assumed income earner stems from the welfare reform movements of the 1960s which gave rise to neoliberalism in American economics. Some reformers, such as Daniel Patrick Moynihan, sought to extend the family wage to Black men. The family wage was intended to give men the financial stability to support a family, a benefit which should not be racially restricted. For Moynihan, female-headed households, which were especially common among African-Americans, were deviant. Extending the family wage to Black men ‘restored’ their masculinity and promoted the idea of the nuclear family.

The poor-law tradition

In the 1970s and 1980s, the nineteenth-century poor-law tradition informed welfare policy. This tradition focused on the family as being the primary responsible agent for taking care of dependents. Families should be self-sufficient. Familial support is a private matter, and families should not rely on the state. These ideas became part of the meaning of personal responsibility under neoliberalism in the 1970s and 1980s. Gary Becker, for example, thought that relying on welfare would erode natural bonds of altruism that existed within families.

The nuclear family as natural

When welfare reform failed to happen, the privileging of the nuclear family persisted. Some critics argue that neoliberalism, unlike social conservatism, lacks a moral ideology. But Cooper suggests otherwise; neoliberalism has an implicit moral philosophy that centers on the family. It “posit[s] an immanent ethics of virtue and a spontaneous order of family values that it expects to arise automatically from the mechanics of the free market system.” The nuclear family is a basic assumption of neoliberalism, a natural feature of society. When markets are strong, families will be strong. When the family structure is threatened, it indicates that something (probably the state) interferes with the free market.

The economic family in Arendt

As much as Arendt discusses home and belonging, what she means by family is muddled for me. One of the clearest descriptions she offers is of the economic family. She takes this model from Aristotle, also adopting his distinction between the private and public realms. The private realm is associated with the household, whereas the public realm is associated with the polis, which refers to the political community.

For Arendt, as for Aristotle, the household/family is pre-political. It does not make sense to talk about freedom at home. The (male) citizen could only enter the political arena if his needs were met. The household (more specifically, women and slaves) took care of these needs. Thus, the patriarch of the household leaves it to become the citizen and to experience freedom with his (also male) peers.

If we can glean a sense of “family values” from Arendt, it would be norms that are wrapped up in maintaining physical life, namely, consumption and efficiency. Whereas these norms are appropriate to the household—after all, one’s needs must be met—they are disastrous for politics. The nation becomes like a giant family, and politics about meeting needs. Arendt’s exploration in The Human Condition and elsewhere of how freedom disintegrates when consumption and efficiency become norms for politics provide powerful insights for critiquing neoliberalism.

The family as natural, again

The Ancient Greek model of the household is not the nuclear family. The two models are related, in the sense of converging around values such as efficiency and consumption.

However, there is another similarity between the family in neoliberalism and Arendt’s accounts. Arendt too assumes the family to be a natural social structure. As such, we need feminist and queer critiques of the family to supplement her views when leveraging them in critiquing neoliberalism.

Gender as essential

Norma Claire Moruzzi discusses the lack of attention to gender in Arendt’s biography of Rahel Varnhagen. Although it is sub-titled A Biography of a Jewish Woman, womanhood is not explicit in Arendt’s analysis. Whereas Arendt discusses Jewishness as constructed identity (think of her discussion of the parvenu and the conscious pariah), gender is something that is private and, ultimately, treated as an essential trait.

I think something similar can be said about Arendt’s treatment of the family. In focusing on the private, she fails to acknowledge ways in which the family is constructed.

The family as a natural force

As she describes in The Human Condition, “The distinctive trait of the household sphere was that in it men lived together because they were driven by the wants and needs. The driving force was life itself” (p. 30). From the outset, then, the family is treated as an essential and natural kind of social arrangement.

The family as patriarchal

To be fair, Arendt notices the patriarchal hierarchy within the Ancient Greek family. Other “family values” are sovereignty and violence. The patriarch’s word is law and can be enforced through violence. But she does not explicitly critique violence within the family itself. In addition, the lack of freedom experienced by women, children, and slaves is merely a feature of the family, not the subject of critique.

For Aristotle, the differences between men (citizens), women (their wives), and slaves is biological. In his Politics, Aristotle describes women as naturally inclined to reproductive and care-giving tasks, while slaves are naturally inclined to performing the labour needed to maintain the household. (I recommend Elizabeth Spelman’s discussion of Aristotle in Inessential Woman). In not actively critiquing Aristotle’s biological essentialism, Arendt implicitly accepts it.

Inequality and injustice in the family

One might excuse this oversight by pointing out that Arendt’s goal is to contrast values of the household with values central to the polis. She is not offering a normative account of the family, but describing a particular model of the family to glean understanding about the public/private distinction. Her discussion of the rise of the social in modernity implies that family structures are not rigid.

Moreover, one might point to the presumption across Arendt’s work that all human beings are equal. The presumption of equality is implicit within her notion of plurality. Thus, she would reject a world where people were deemed essentially incapable of freedom on the basis of gender, class, or race.

This defense seems lukewarm, however, when someone is using Arendt to critique neoliberalism. Failing to attend to class, racial, and gender hierarchies that are embedded in notions of family mean that we cannot fully understand how neoliberalism operates. This is a main thesis of Cooper’s book. I think Arendt’s critique of the family has much to offer feminist theorizing, but she must be read alongside feminist and queer critiques that expose the ways in which injustice, not just inequality, structure it.

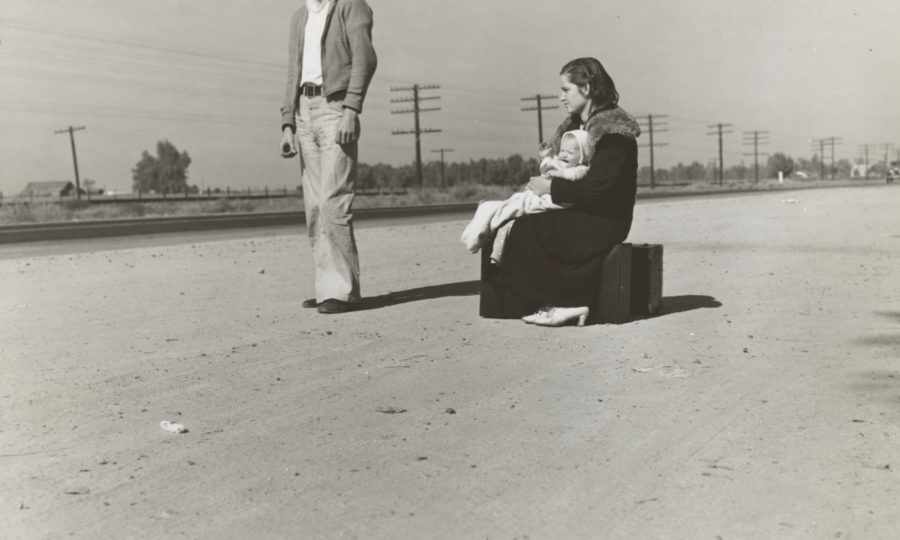

Photo by The New York Public Library on Unsplash