When a vegan and a cattle farmer share a table

I sat down at a table, my plate piled high with grape leaves, hummus, baba ganoush, pita, green salad, and quinoa salad. The person sitting next to me was complaining about plant-based options like the Beyond or Impossible Burger compared with beef. “They’re processed. It’s not good for you. not like beef.”

Putting aside questions about “healthy,” I thought this remark missed the point. I pushed, trying to expand the conversation beyond individual decisions about health to broader, systemic issues. “I’m not sure the main point of these options is to be healthy. If you’re buying a fast food burger, ‘health’ seems to be a less relevant issue. I think these options are about reducing meat consumption. For climate change.” (Side note: Pat Brown, Impossible Foods founder and CEO, tends to put the climate impacts of animal agriculture at the front of Impossible Foods’ mission.)

The conversation drifted. “So what do you do?” I asked the person who’d been lamenting about the turn away from animal-based burgers. “I raise organic, grass-fed beef cattle.” Maybe that explains why someone has anxiety about Beyond and Impossible burgers. They’re competition.

“Earth is a microbial planet”

Apart from awkward holiday meals with my aunt and uncle, I don’t often meet cattle farmers. This exchange occurred at the “Re-imaging Human Health: A Symposium on the Microbiome,” hosted by the Hannah Arendt Center for Politics and Humanities (among other groups), where I am spending my fall semester.

The Symposium brought together a number of experts to discuss how the loss of biodiversity, particularly with the microbiome, was impacting medicine (human and animal) and farming (plant and animal). The experts included physicians, researchers, pharmacists, veterinarians, policymakers, science educators, and farmers.

I left the symposium having learned much about the microbiome (and about poo). Part of what it means to be a human being is to have microbial bacteria. But it’s not uniquely human; animals, plants, the soil all have microbiomes too. As toxicologist and immunologist Rodney Dietert put it, “Earth is a microbial planet.”

Though I learned about advances in our (still) nascent understanding of the microbiome and its significance, I left the conference disappointed by how climate change wasn’t a prominent theme. Even though “systems thinking” was a buzz word throughout the weekend, many of the panels focused on connections between farming practices and human health, but not larger questions about climate health.

Antimicrobial resistance

There was quite a bit of attention on antibiotic use. Short story with respect to agriculture: Food is grown with chemicals that contain an antibiotic, glyphosate. This food is fed to people and to animals. (Antibiotics have also been added to animal feed rather than having medicine and quarantine provided to individual animals who are sick. This practice was banned in the United States in 2017, though some participants suggest it still occurs). Antimicrobial resistance is on the rise.

Consumers to the rescue!

The vets and farmers tended to focus on collaborative solutions, working to improve agricultural practices. Policy makers talked about getting industry to invest in agri-ecological research. There was also talk about “voting with your dollars.” Consumers can shape the industry by creating a demand for products grown without reliance on antibiotics or on the kinds of bad antibiotic practices that contribute to microbial resistance. They must be willing to pay the premium for the increased labor (et cetera) costs of “natural” meat.

Buy organic beef! Buy grass-fed beef! Support your local farmer! Meet local your farmers and learn about their practices, as organic certifications may not be for everyone. (There was some talk about economic privilege and access, but I’ll bracket that here).

Buying or organic or buying local doesn’t address the larger systemic problems. Farmers have turned to antibiotic overuse because of economic pressures. As one of the veterinarians remarked, “I don’t want to beat up on my clients and my friends.”

Everyone deserves a decent livelihood and meaningful work. But that doesn’t preclude the question: maybe a viable solution to antimicrobial resistance in animal agriculture is to have less animal agriculture. When climate microbial health is added to this issue, my question seems even more pressing. Even the United Nations recently recommended reducing animal consumption! At the Symposium, no one connected animal agriculture to climate concerns.

The ambiguity of putting your dollars behind your beliefs

I feel a deep tension about consumer actions and climate responsibility. I’ve criticized it above, yet I make choices according to a sense of consumer responsibility. I want my daily living to align with or reflect my beliefs. When at home, I make most of my food from scratch and shop at zero waste bulk stores to reduce my reliance on packaging.

And, consumer actions can lead to larger-scale change. For example, today at the Bard College Climate Strike I learned that two of the students’ demands were that the college divest from fossil fuels and increase plant-based options in the cafeteria. These both seem to be to be an important concerns for consumer action for institutional change. (Or stakeholders action? Students are hardly mere consumers.)

Thinking as a community

Another key message that I took away from the Symposium is that we need to think as a community. Perhaps I found the dialogue lacking because the community was narrowly conceived as people or industries invested in maintaining animal agriculture. Maybe I lacked imagination in not raising some of these questions from the audience.

If any direction seems promising, it’s thinking as a community. Economics is one concern (indeed, the most convincing argument for divestment might be the economic one), but not the only concern that brings communities together. I’m still chewing on what role consumer actions might play in addressing systemic problems.

Credits

- Watch videos of all the panels and find other materials from “Reimagining Human Health” here.

- The feature photo by Markus Spiske on Unsplash.

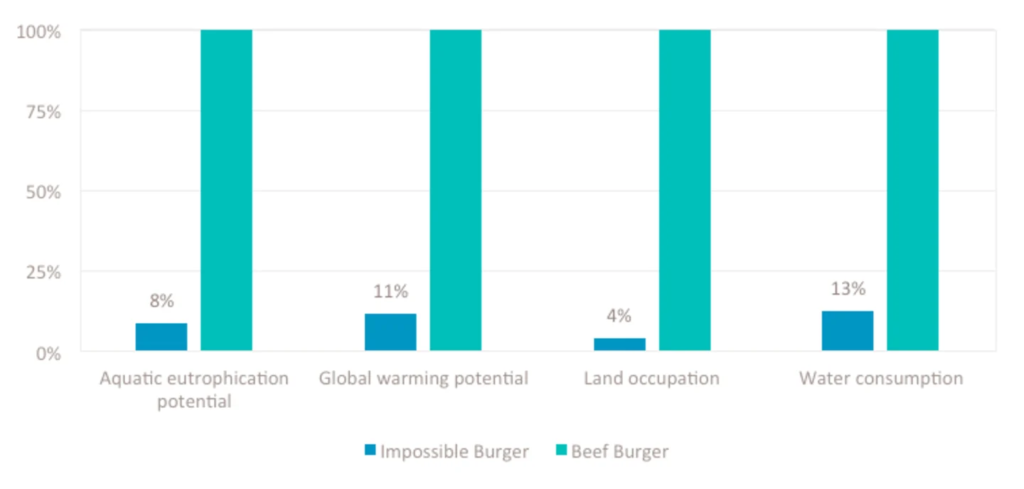

- The chart is from Impossible Foods 2019 Environmental Life Cycle Analysis.

- I took the climate strike photo at the Bard College Climate Strike.