“When are things going to get back to normal?” is a question I hear often. Others point out that “normal” will be drastically different. On April 27, Ontario released A Framework for Reopening Our Province. The plan emphasizes the slow and the incremental. I imagine what changes I will encounter in the future: Will a server take my temperature before I enter a restaurant? At the movie theater, will there be several empty seats separating me (and the popcorn bucket) from my friends? Will I wear a face mask when I leave my house for the an indefinite period of time going forward?

I’m part of a kitchen co-op that organizes large community dinners. We’ve been talking about whether people will even want to attend a community dinner when large gatherings are allowed. Some of our previous attendees say they don’t want to attend a large gathering until a vaccine has been developed. According to a Nature review, a vaccine could take as long as eighteen months to develop, not considering the time needed to distribute it.

The new normal

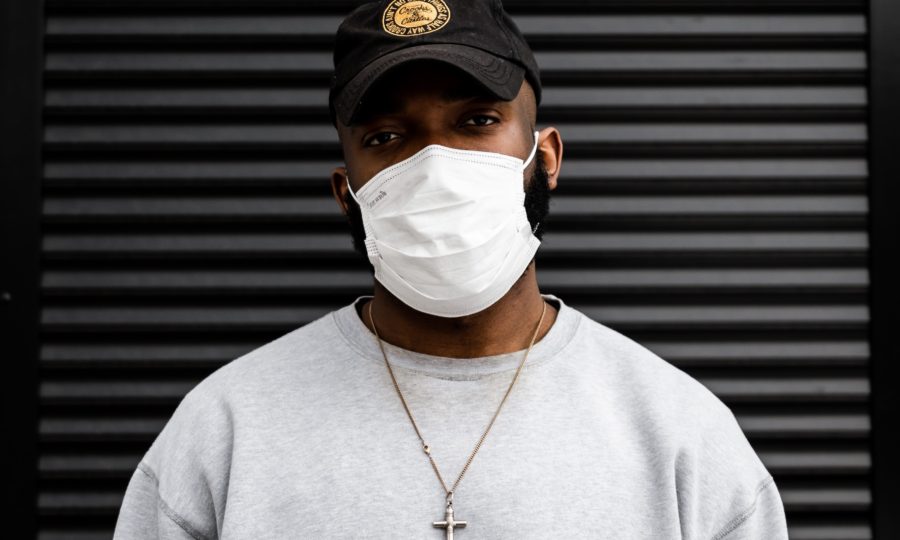

One idea I’ve heard repeatedly is that the use of non-medical face masks will become more normalized across Canada. Masks primarily protect others from you, and your potentially infectious respiratory droplets. In early April, Globe and Mail health reporter André Picard wrote, “Increasingly, however, making and wearing a mask in public is becoming a demonstration of civic-mindedness, a public acknowledgment of the risks coronavirus poses, and a fitting symbol for the new normal.”

A few weeks ago I distributed take-away meals with Food Not Bombs. When I was distributing food with Food Not Bombs a few weeks ago, I told someone that my face mask was hiding my smile from them.

Un-dividuals

Philosopher, curator, and activist Paul B. Preciado, drawing on theorists of biopolitics, argues that the management of Covid-19, both through disciplinary measures to promote isolation and through technological surveillance, produces a new mode of subjectivity. I find his language of the “un-dividual” intriguing:

The subjects of the neoliberal technical-patriarchal societies that Covid-19 is in the midst of creating do not have skin; they are untouchable; they do not have hands. They do not exchange physical goods, nor do they pay with money. They are digital consumers equipped with credit cards. They do not have lips or tongues. They do not speak directly; they leave a voice mail. They do not gather together and they do not collectivize. They are radically un-dividual. They do not have faces; they have masks. In order to exist, their organic bodies are hidden behind an indefinite series of semio-technical mediations, an array of cybernetic prostheses that work like digital masks: email addresses, Facebook, Instagram, Zoom, and Skype accounts. They are not physical agents but rather tele-producers; they are codes, pixels, bank accounts, doors without names, addresses to which Amazon can send its orders.

Preciado’s description of this post-Covid-19 subjectivity acknowledges neoliberalism’s entrenchment of the individual and also the existential loss of being with others in public. The unique “who” of a person, as Arendt might say, becomes obscured. Instead, we encounter—and protect against–others as potential infections to personal space.

Listening with the body

Unrelated to Covid-19, Janet and I recently read an article by philosopher Sophie Bourgault on how social justice requires attentive listening, and neoliberalism undermines the opportunities for attentive listening and the development of attentive listening skills.

Bourgault argues that listening is an embodied act. Physical presence “adds a layer of complexity to the act that reading a letter or a book cannot replicate” (p. 317). For Bourgault, physical presence allows a listener to attend to embodiment. Non-verbal cues are crucial aspects of attending to what is being communicated by an interlocutor, and to how the listener expresses their focus and receptivity.

Our democratic engagement requires attentive listening, especially when conversation partners occupy different positions of social power. For example, certain kinds of greeting signal our receptivity to engage with others politically. Bourgault references Iris Marion Young on this point: Greetings, said with a certain comportment, a handshake, (debatable perhaps, even pre-pandemic), or a smile might signal to someone your willingness to listen to what they have to say. (Can I add the Vulcan salute here, appropriated from a Jewish blessing?) For Young, greetings indicate a willingness to trust, to enter into a relationship and conversation. (I’ll put the matter of superficial greetings and the manipulation of trust to the side for now).

Anxiety about masks

Although Bourgault is pluralistic when she talks about embodied cues and listening, perhaps my mind went to facial expressions and masks because of COVID-19. Preciado’s picture of the faceless masked un-dividual invites questions about how public appearance will change in the “new normal.”

Already my questions are laden with cues about my social location—for me, wearing a non-medical mask is unfamiliar. However, in some communities in Canada non-medical face masks are more common. In Western liberal democracies, we tend to put emphasis on the face, especially the mouth, as a way of capturing the authentic appearance of the other. But, as political scientist Katherine Bullock recently reminds us, the actors on Grey’s Anatomy, which is in its sixteenth season, convincingly portray the emotional richness of their characters even when their faces were covered with surgical masks.

Racism and anxiety

We often use the face as a reference point for good citizenship. It is an assumed requirement for civic dialogue and togetherness. This assumption motivated racism towards Muslims in Canada when Jason Kenny, in his previous role as Immigration Minister, tried to ban the wearing of niqabs in citizenship ceremonies. This assumption also emerged last year when Quebec passed Bill 21. Faces are considered dangerous, Bullock argues, when covered. Except, of course, in the winter, when many of us cover our faces with scarves or balaclavas. When it comes to masks, it’s really brown faces, Muslim faces, that are considered dangerous. (Something similar is going on in France, which now requires people to wear non-medical masks on public transportation. However, the French government bans the public wearing of burqas.)

Something similar is happening in the United States. For example, a Dr. Armen Henderson, who is black, was handcuffed by a police office upon leaving his home to provide Covid-19 tests to unhoused people. Henderson wore a mask, the police office did not. Like Bullock’s argument about the niqab, Henderson’s masked black face was perceived to be dangerous. What happened to the solidarity Picard mentions in wearing masks to protect our fellow citizens from one’s own potentially infectiousness?

Embodied listening with masks

Bourgault argues that embodied listening is hard work. It takes focus and time to attend to another’s embodied cues in addition to their speech. The question I ask myself isn’t whether others can see my “smile” despite the mask, but how will I listen attentively to their embodied cues? How do I adjust the way I signal to others that I am receptive and listening?

In the Human Condition Arendt provides a broad definition of a polis, her term for political community. A polis emerges whenever people speak and act together. Nothing about wearing face masks, that I can tell, necessarily destroys our ability to speak and act together. However, Bourgault’s discussion of neoliberalism may help explain why we feel anxious about face masks and public appearance. Neoliberalism has a “love of increased speed and of information and communication technologies” (p. 330).

My over-reliance on the face as the central mode of embodied expression probably speaks to neoliberalism’s pressure to speed us up. Because I’ve been raised in a society that emphasizes the face, I unreflectively conflate attention with attention to the face/mouth. It’s quick and easy. A public realm with more medical face masks will encourage me to slow down and pay attention to embodied cues that I usually pass over in my emphasis on facial expressions.

The new normal will encourage some of us—people like me—to learn to listen more expansively. Perhaps a slower-paced, more attentive listening to others should also become part of how we show solidarity during and after the pandemic.

Credits

Photo by Wells Chan on Unsplash