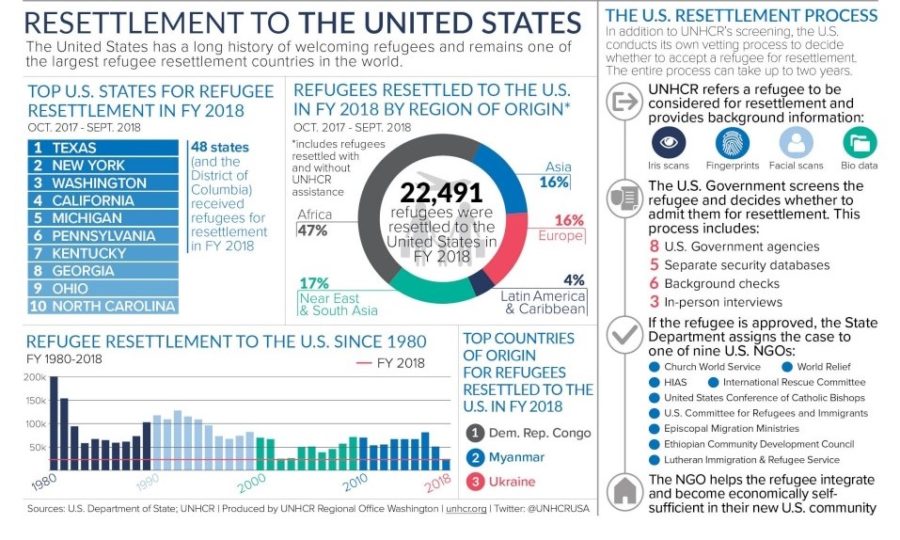

It was chilling to read about Texas Governor Greg Abbott’s statement that Texas would not resettle refugees in 2020. In recent years, Texas has been the state to resettle the largest number of refugees.

Echoes of Arendt’s Origins of Totalitarianism

The Governor’s decision reminds me of Hannah Arendt’s discussion of the decline of the nation-state in the Origins of Totalitarianism. The phenomenon of statelessness tested the limits of national sovereignty. Some states stripped their unwanted citizens of their citizenship–a phenomenon Arendt argues was not seen before the twentieth century.

National sovereignty

National sovereignty usually is taken to be a given, especially in matters of citizenship and borders. However, Arendt says that “practical consideration and the silent acknowledgement of common interests restrained national sovereignty until the rise of totalitarian regimes” (p. 278). Those regimes emphasize national interests above the interests of the common–the international community in this case. These interests eroded the right to asylum, which Arendt describes as “the only right that ever figured as a symbol of the Rights of Man in the sphere of international relationships” (p. 280).

The Minority Treaties

These tensions were seen earlier as well, in the Minority Treaties of 1919 and 1920. These treaties conferred rights on national and cultural minorities within states, some of which had been newly created following the First World War. But, the minority treaties were guaranteed by the League of Nations. This move indicates that nation-states had not sufficiently protected the human rights of minority groups. Rather than redress a problem stemming from nationalism, the Treaties reinforced nationalist ideas:

The minority Treaties said in plain language what until then had been only implied in the working system of nation-states, namely, that only nationals would be citizens, only people of the same national origin could enjoy the full protection of legal institutions, that persons of different nationality needed some law of exception until or unless they were completely assimilated and divorced from their origin. (p. 275)

Although naturalization is one mechanism a nation-state can use to confer legal protections on newcomers, Arendt suggests that nationalist anxieties were a barrier to naturalizing groups of stateless peoples. Previously naturalization had been intended for individuals who needed to flee their home country, not for masses of stateless people needing a new home. Nation-states worried that naturalizing the stateless would reinforce minority solidarity and prevent national unity within the state. But the newcomers are the ones who suffer: “The difference between a naturalized citizen and a stateless resident was not great enough to justify taking any trouble, the former being frequently deprived of important civil rights and threatened at any moment with the fate of the latter” (p. 285).

Nationalist anxieties

These nationalist anxieties arise in Gov. Abbott’s decision for Texas to reject refugee resettlement. His statement expressly links refugee resettlement to immigration issues. In Canada, we are used to thinking about refugee resettlement alongside immigration. Canada’s resettlement policy is folded into immigration policy. But this is not what Abbott is doing. He uses the need for immigration reform as a reason to limit refugee resettlement. This connection shores up ideas that “Texan-ness” must be protected, whether from people crossing the border or from refugees.

The dominant image of an asylum seeker crossing the US-Mexico border is probably of a Latinx person or family. This image does not represent the likely nationality of a refugee. Of the top ten countries of origin among resettled refugees in the US, only one is a Latinx country (El Salvador). It seems to me that all non-White people are lumped together in this kind of move. It also presumes Texas is a “white” state, though the Latinx population is close in numbers to the White, non-Hispanic population. (Caveats here about how racial groups are described in the census data, and how mixed race identities are often ignored).

State sovereignty

Gov. Abbott’s decision was facilitated by an Executive Order issued in September 2019 which requires State and municipal governments to consent in writing to receive refugees. (Refugee agencies are suing the President, arguing that the Executive Order violates federal law.) And it must be both; a willing municipality cannot resettle refugees if the State government withholds consent. The tensions arising with national sovereignty are reproduced by the Executive Order, which enables States to define refugees as not-like residents of the State.

I’m not competent to get into questions about the limits of the sovereignty of States. But, I think it sufficient to say that States are unlike nation-states in being granted such authority over their own borders. The federal government is also not like the League of Nations. The Executive Order serves as a way for the federal government to passively excuse itself from its responsibility to protect refugees.

Family matters

Because my research project focuses on Arendt’s critique of the family, questions of family usually come up for me when I think about refugee resettlement. In past posts, this blog has detailed ways in which I find family metaphors to be unhelpful in describing refugee resettlement and political belonging.

But families are important. The loss of family, not only the loss of a physical home and national belonging, contributes to refugees’ rootlessness. Thus, family reunification is an important dimension of refugee resettlement. Given the number of refugees currently resettled in Texas, the decision not to admit more refugees threatens reunification efforts.

I’ll be paying attention to how the lawsuit against the Executive Order proceeds.

Credits

Feature photo from the UNHCR.