I live on the traditional lands of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg and Haudenosaunee peoples.

I think it’s a little pathetic that I can’t spell, from memory, the names of the Indigenous nations that live(d) in this region. I’m working on that.

In early June I attended the Congress of the Humanities and Social Sciences, an annual meeting of various disciplinary academic associations. Although I attend Congress regularly, I have rarely have attended sessions hosted by non-philosophy associations or the host institution. This year I did, which afforded me an opportunity to hear diverse examples of acknowledging the land: that the University of British Columbia is situated on the ancestral, traditional, and unceded lands of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam) people.

Hearing the land (or territorial) acknowledgment offered often, and offered differently, encouraged me to reflect on the acknowledgements I include on my syllabi.

I also realized that I don’t have a land acknowledgment on this blog or my website. Another project.

Why land acknowledgements

Reading this post, you will get a sense about why I do land acknowledgments. Briefly, I include them as part of my teaching practice as I seek to decolonize my feminist politics as a white settler scholar.

Many institutions and community organizations now offer land acknowledgements, following from the Calls to Action (2015) issued by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Acknowledging the land is one way, for example, of responding to the call to reject colonial concepts such as the “Doctrine of Discovery” and “terra nullius,” and to respect and renew treaty relationships.

If you are unfamiliar with land acknowledgments, and why educators increasingly include them in institutional settings, let me point you to a few resources that I find to be helpful introductions.

- Read Lori Campbell’s opinion piece in the Waterloo Record on land acknowledgments in Waterloo Region. Lori Campbell is the director of the Shatitsirótha’ Waterloo Indigenous Student Centre at St. Paul’s University College.

- Read this post by âpihtawikosisân on land acknowledgments in universities, and the need to go beyond them. Readers of this blog know from a previous post that I’m a big fan of âpihtawikosisân’s work.

- Read the this primer for settlers by Shannon Dea on the UWaterloo Faculty Association’s blog.

- Read the UWaterloo Arts Faculty statement about why and when we (i.e., Arts faculty members) use acknowledgements.

A rubric for land acknowledgments

Recently, I was reminded by a colleague of the Territorial Acknowledgement Rubric developed by kwe plain. I decided to use this resource as a way to assess my land acknowledgments. Before reading further, follow the links above to kwe plain’s blog and study the rubric, which uses a numeric breakdown familiar to students who have studied in Canada (90-100=A+, 80-89 =A, 70-79 = B, et cetera).

WS 101 Syllabi

Because I’ve taught WS 101 several times, and syllabi usually begin with a copy of the previous iteration, I thoughts these syllabi would be an easy way to track how my territorial acknowledgment has changed.

Fall 2016

I listed this acknowledgment on page 2 of 11, under the “learning goals” and before “learning methods.” My teaching assistants agreed with me including this statement, and so the “we” refers to the three of us as an instructional team.

Special note: Because “colonization” is one of the key concepts we’ll be discussing in WS 101, the instructional team would like to acknowledge that we are on the traditional territory of the Attawandaron (Neutral), Anishnaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. The University of Waterloo is situated on the Haldimand Tract, land promised to Six Nations, which includes six miles on each side of the Grand River.

Winter 2018

This acknowledgment appears on page 1 of 9, included in the section with information about my office location, contact details, et cetera for me and the teaching assistant.

Feminist politics works to end all forms of oppression. Thus, acknowledging the history of and ongoing forces of colonialism are important dimensions of feminist politics. The instructional team would like to acknowledge that we are guests on this land. We are on the traditional territory of the Attawandaron (Neutral), Anishnaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. The University of Waterloo is situated on the Haldimand Tract, land promised to Six Nations, which includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Read more about the Haldiman Tract here.

Did you find the typo? Yep, embarrassing. That typo also appeared in the acknowledgement in my email signature. I discovered it when drafting this post. I think that mistake alone probably earns me a 50 according to the rubric!

Winter 2019

The placement of this acknowledgement is the same as the one for Winter 2018.

As a professor at the University of Waterloo, a settler, and an immigrant to Canada, it is important for me to acknowledge that our campus community is the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishnaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. The University of Waterloo is situated on the Haldimand Tract, land promised to Six Nations, which includes six miles on each side of the Grand River.

Comparing the land acknowledgements across my WS 101 syllabi

- I situate myself in terms of my social position to a greater extent in later iterations. The 2016 version presents “colonization” as an important theoretical concept, whereas the 2018 version connects colonization with feminist practice and makes reference to ongoing forces of colonization. In 2019, maybe because I did not have a TA, I identify myself as a settler and an immigrant, alluding to a tension I feel between decolonization, settler responsibility, and immigration as a white settler (see my previous post about privilege and immigration status).

- I include, then drop, the language of “guest.” I have heard “guest” language used in ways I find helpful. For example, at Congress an Indigenous person who was not from one of the nations that call Vancouver home called herself a guest. This language expressed the person’s thanks for the welcome of the UBC Indigenous Education program and the First Nations Longhouse. In a talk I attended, feminist theorist Erin Wunker uses this language in describing her relationship with a friend who is Indigenous, a personal relationship which informed her sense of her settler responsibility. I think my use of “guest” was presumptive, so I moved away from it. Perhaps that’s another reason why I identify myself as an immigrant, to situate how I see my responsibility in relation to Indigenous people’s and my responsibility for decolonization/Indigenization/reconciliation. These three terms are not synonyms. I merely list them all because I’m working through what settler responsibility means for me.

- All iterations of the acknowledgment name Indigenous nations, but only include a settler-Indigenous treaty rather than pre-settlement treaties. I also present a fairly simplistic binary between settler and Indigenous people which does not clearly identify white privilege/white supremacy.

- In 2019 I use the language of “the Neutral people” rather than “the Attawandaron (Neutral) people.” Both “Neutral” and “Attawandaron” are names given to this nation by settlers, but after learning about the history/meaning of “Attawandaron,” I stopped using that term. I rarely see it nowadays.

- The 2018 version connects to resources. That seems helpful. In one course, I created an online resource with links about lank acknowledgements.

Thoughts for improvement, using the rubric as a guide

- Be more explicit in naming Indigenous nations. For example:

- Mention that the Six Nations are part of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy.

- Perhaps include notice that the Neutral people were destroyed through colonization.

- Expand the discussion of treaties.

- Include treaties between Indigenous nations, that were later extended to include settlers, such as the Dish with One Spoon Treaty. kwe plain has another post that discusses the importance of expanding the way we refer to treaties.

- Make explicit that settlers are treaty peoples too.

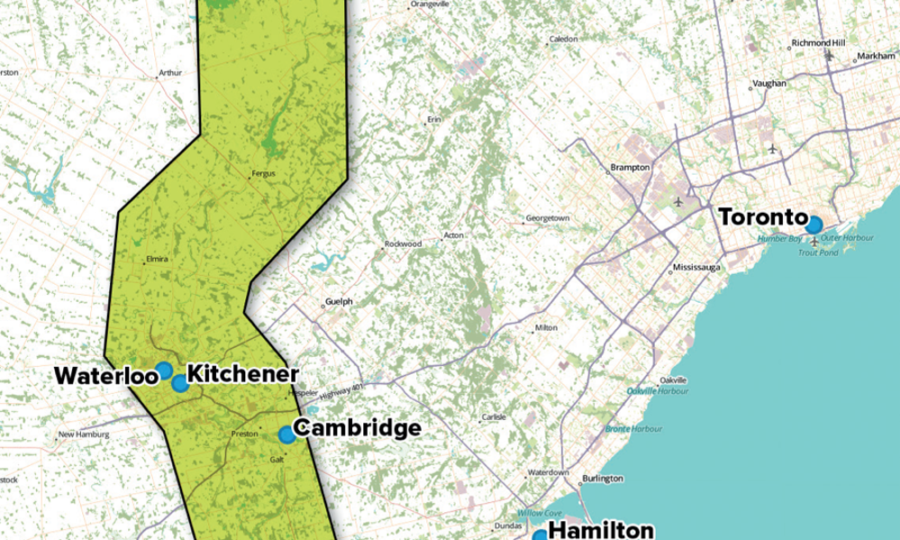

- Include more specific information about the Halidmand Tract, for example, that UWaterloo is on Block 2. (See this map which lets you explore the blocks).

- Acknowledge on-going forces of colonialism.

- As the report from the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, released this month, makes clear, settler colonialism has not ended.

- As a feminist educator, I think it’s important to think about inter-generational trauma related to residential schools and assimilating forces of education more broadly.

- Distinguish between how white privilege/white supremacy is implicated in settler colonialism versus how non-Indigenous, non-white people are related to settler colonialism. My immigration story will be different in terms of its connection to histories of domination than that, say, members of the African diaspora or South Asian immigrants whose families may have originally migrated to Canada for work.

Why the self-assessment?

Continual reflection on our practice is essential for feminist politics. But also, I want make this reflection a public exercise for two reasons. First, I want to share some resources I find helpful, like kwe plain’s rubric. Second, I want to make myself accountable for doing better. I’m not going to get this perfect on the fourth try. Even with the improvement ideas listed above, I’m only moving up incrementally on the rubric. I won’t be close to the kind of decolonizing statement that plain suggests is necessary (see the “90” and “100” categories on the rubric).

Further, as I am sure we all know, land acknowledgments are important part of cultivating a feminist classroom. But they only one part. That being said, being intentional about land acknowledgements prompts me think about other aspects of my teaching practice that might be improved. While I’m sharing resources, here’s another reading suggestion: Janice Barry’s interview with Indigenous students at UWaterloo about what they want faculty to know.

If you have thoughts about other areas of improvement related to land acknowledgments, or points of dialogue, I welcome them.

Eli Clare’s example

In closing, I’ll share a few lines from the poet/essayist/theorist/activist Eli Clare. He weaves acknowledgements of the land into his work in ways I find meaningful and authentic. Though I dislike the word “authentic, philosophically, what I mean here is something along the lines of “non-awkward,” and “non-forced,” and “relevant.”

The following, from “White Pines,” is one of many examples from Clare’s recent book, Brilliant Imperfections. This piece begins with the British Navy (circa the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries) claiming ownership of white pine trees that exceed 100 feet in height.

Now, two centuries later, I camp among white pines in

occupied Abenaki Territory–known for the time being as

Vermont–my favorite tent site at Ricker Pond strewn with

needles. (p. 1)

Photo credit

The map of the Haldimand Tract was published in Alternatives Journal.